In my years of following Batman, the massive piles of issues, stacks of trades and meticulously calculated opinions on storylines, plot developments and the writers and artists that defined the character, I was sure of one thing.

Frank Miller was king.

I’ve written before that Miller has long been one of my idols in the comics industry. He wrote and drew violent, hard boiled and whip smart stories of brutal heroes who remained just slightly more ethical than the villains they took on. His twin masterpieces, “The Dark Knight Returns” and “Batman: Year One” virtually defined the Bronze Age as well as the brooding and troubled hero that Bruce Wayne would become.

Looking back, it is abundantly clear as to why I so deeply associated with Miller’s take on the character. I grew up with comics desperately wanting to be taken seriously. I wanted one of my favorite stories to be viewed as something adult and interesting and something that I could show off. When Image was marketing little but unmitigated id with guns and massive cocks, I wanted a Batman that was doing all that he could just to survive for another day.

That makes it all somewhat surprising that the man to tear down one of the most innovative storytellers in comics was a filmmaker who distilled nearly 30 years of comics history into a smart, dangerous and hopeful movie. Christopher Nolan’s high profile and well received take on Batman was able to show off an adult take on comic films with “Batman Begins” but he really showed off what he wanted to do in “The Dark Knight,” most likely the movie he will be best remembered for.

Initially, it seems as if Nolan’s take on the character owes much to Miller’s hyper-violent Batman but that’s strictly a cover-up. Nolan embraced the darkness of Gotham in order to make a compelling product, yes, but he ultimately was setting up something even more ambitious, a Batman that genuinely is interested in bringing light to Gotham. I think most people forget about the quietest moments of “The Dark Knight” in favor of loving Heath Ledger’s performance as the Joker but for me, Aaron Eckhart stole the show as Harvey Dent and his line, “the night is always darkest just before the dawn and the dawn is coming,” is the most telling moment of the film. For Nolan, chaos is temporary, Batman is forever.

I have my fair share of complaints about “The Dark Knight” but Nolan’s theory that darkness pushes people to justice rather than corruption pushing us to anarchy is a potent one. Whether it is the rejection of mutually assured destruction on the boats, the sainthood of Harvey Dent or Gordon’s sense of hopelessness as he destroys the bat signal, this is a film about people being pushed to the heights or heroism by the darkness they are forced to oppose.

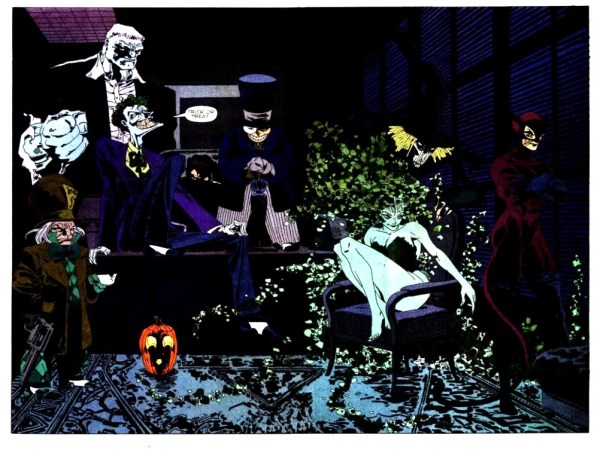

Nolan made no secret of drawing extensively from Jeph Loeb’s “The Long Halloween” when he and David Goyer wrote the first two films of his trilogy and the evidence is clear, particularly in “The Dark Knight.” The partnership between Dent, Gordon and Batman, men and women powerlessly watching as an empire crumbles and the ethical ambiguity of fighting crime is all prominent in “The Dark Knight” and shows clearly the cost of fighting monsters. The end of Nolan’s masterpiece even parallels the ending of Loeb’s classic, with Batman and Gordon both wondering what the cost of fighting crime is when they’re forced to lose their brightest of heroes.

Nolan made no secret of drawing extensively from Jeph Loeb’s “The Long Halloween” when he and David Goyer wrote the first two films of his trilogy and the evidence is clear, particularly in “The Dark Knight.” The partnership between Dent, Gordon and Batman, men and women powerlessly watching as an empire crumbles and the ethical ambiguity of fighting crime is all prominent in “The Dark Knight” and shows clearly the cost of fighting monsters. The end of Nolan’s masterpiece even parallels the ending of Loeb’s classic, with Batman and Gordon both wondering what the cost of fighting crime is when they’re forced to lose their brightest of heroes.

Through all of this, Nolan directly contradicts the world Miller created, prominently displayed in “The Dark Knight Returns.” For Miller, anarchy creates anarchy, spawning lawlessness and corruption in a never ending cycle of pain, misery and death. Nolan dares to be positive in the face of chaos. Where Miller’s Batman is forced to brutally murder his archnemesis in a fun house, Nolan’s leaves the Joker hanging. Miller’s Batman is defined by the never-ending battle against crime, Nolan’s knows that the a future is more important than the pain.

The words “I believe” loom over Loeb’s “The Long Halloween” and equally haunts Nolan’s “The Dark Knight.” Bruce Wayne believes in Gotham, Gilda Dent believes in Harvey Dent, Alberto Falcone believes in Holiday; these are hopeful men and women, even when they’re in the worst places possible. In comparison, the only word that looms over the works of Miller is “goddamn,” in sentences like “I’m the Goddamn Batman” and so many others.

As I prepare for the premier of “The Dark Knight Rises,” I’ve been going through many of the Batman classics and I’ve had to go back to many of Miller’s most well known works. Rereading “Year One,” “The Dark Knight Returns” and the fairly awful “All Star Batman and Robin,” I’ve been struck hard by how violent, ugly and pessimistic these stories are. In the last few years, great writers and artists such as Scott Snyder, Grant Morrison, Frank Quietly, Paul Dini and Jeph Loeb have given us a Batman with pathos, one that is sometimes required to make the hard choices but isn’t defined by them. I don’t want a Batman who has to be one with the night, Nolan and many others have helped to show that the best Batman may be the one that may be able to walk away from the darkness.